Discovering the tourist charms of Tychy

[text by Irma Kozina, photos by Adrian Larisz]

A few years ago newspapers in the Upper Silesia initiated a debate on the urban structure of Tychy – one of the youngest industrial cities of the region. It was then that historians discovered a mysterious plan from the time of the Third Reich, on which the occupying Nazis marked a new object – a settlement located in the heart of the industrial agglomeration which role was to relieve the overpopulated centres of heavy industry. It was to be a new city with the layout resembling the one proposed after the war by Polish urbanists carrying out the objectives of the six-year plan. Is this resemblance just a coincident? There seem to be no definite answer. One thing is certain, however: no matter what the origin of the layout is, the today’s Tychy is a unique achievement of creative architects skilfully implementing the political and economic ideas of the Peoples Republic of Poland. The tourist attractiveness of the city has been the inspiration for creating a guidebook which is free and available online to anyone interested.

The over 25-thousand city, established in the vicinity of an old brewery formerly belonging to the family of the princes of Pszczyna is often unjustly nicknamed a big workers’ dormitory. Its post-war history starts with the first letter of the Latin alphabet – the ‘A’ Estate designed by the outstanding architect Tadeusz Teodorowicz Todorowski. Educated before the war, this graduate of Politechnika Lwowska (the Lvov Technical University) managed, to some extent, to outwit the socrealistic investor. Since 1950 he adopted a symmetrical layout with buildings grouped around a central square thus avoiding the monumental scale, so typical for the housing districts built at the same time in Warsaw and Cracow. In the middle of the square there is a community cultural centre with two classically composed wings, performing a residential function. In accordance with the socrealistic doctrine in force at the time, the point of reference for Todorowski was in the Reneissance, consequently his square resembles to some extent Michelangelo’s Capitoline Square. It extends itself into an internal street finished with a monument by Stanisław Marcinów of a woman bricklayer holding a brick trowel and a miniature building. The figure embodies the new idea of woman who assumes the role of builder and recreates the world ravaged by war.

The size of the A Estate disappointed the party officials who had expected a monumental venue for party celebrations. New designers were appointed to the task through a competition. Initially, Hanna Adamczewska and Kazimierz Wejchert, the Warsaw architects, wanted to realize a socrealistic project featuring a huge square with the headquarters for the party and city authorities and a wide avenue to be used for rallies and May Day marches. In the wake of the 1956 thaw they abandoned socrealism for unadorned concrete panel blocks of flats – a style called soc-Functionalism by experts. Their housing estates, marked with the subsequent letters of alphabet had a rather monotonous form, enlivened only by a few features such as the Sun Gate, a pyramid shaped building housing a library, a sports hall or the Town Hall consisting of three buildings laid out on the plan of the letter Y. The monotony is successfully broken by the sacred architecture designed by a city resident, the architect Stanisław Niemczyk. His Holy Spirit church is considered by many people the most interesting religious building in the post-war Polish architecture. Its construction began in 1978. The first element of the temple complex was the lower chapel with a round glazed opening in its roof. Standing by the altar, the priest celebrating the mass has it at his feet while over his head there is a skylight in the upper church roof. This symbolically accents the vertical dimension and the metaphysical route which leads a man towards divine light. As for a project built in the communism era, the church amazes us with uniqueness of its form. Outwardly, it resembles a huge pyramid as the architect decided on a square plan with undivided space covered with a dominating wooden roof. While inside, one can notice that the roof is supported by a reinforced concrete structure, acting like a frame of a gigantic tent. Half of the inside roof surface is covered by Jerzy Nowosielski’s icons (the artist died several years ago) depicting the work of the Holy Spirit in the Old and New Testaments. The congregation facing the altar may contemplate a flatly painted, Byzantine like and dignified portrait of Madonna, whose slightly elongated face is contrasted with her robe by use of soft chiaroscuro modelling. Her eyes seem to be looking into some metaphysical space which has been taken out of reality and which makes it impossible to abolish the border between Heaven and Earth. From the nimbus around her head comes a light blue ray and goes to a medallion with a representation of the Holy Spirit dove. This symbolic depiction of the Annunciation is accompanied by the Crucifixion on one side and the Transfiguration on the other. Between them and Mary there are prophets and scenes from the Old Testament representing the work of the Holy Spirit, with the Three Men in the Fiery Furnace from the Book of Daniel as one of the most prominent episodes. The uniqueness of the church located in the district of Żwaków consists also in the specific ecumenism which juxtaposes the paintings rooted in Byzantine and Russian traditions with the allusions to Judaism, here assuming the form of lamps shaped like inverted menorahs. Niemczyk managed to create space with unique atmosphere which is capable of separating you physically and psychologically from the everyday reality and inducing you to pray.

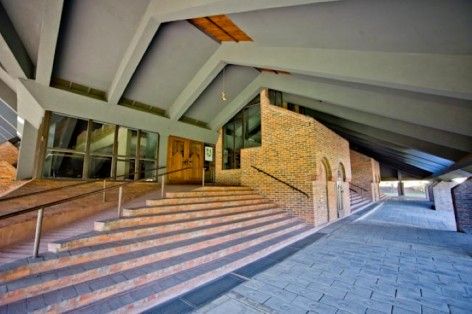

Having lived in Tychy for some time, the artist aimed at introducing certain diversity into the urban tissue of his city, where concrete housing estates may leave one with the feeling of monotony caused by the uniformed style, typical of the Polish 1970s. He may have been even more determined to achieve that while designing another Tychy temple –Sts Francis and Clare church. This church and monastery complex has not been completed yet but, even in its current state, the architecture arouses a lot of interest from visitors. It has been laid out on a plan of a Franciscan cross and it features five towers symbolising the five wounds inflicted upon Christ during the Crucifixion. The whole construction is made of Libiąż stone, the material resembling dolomite used by St Francis in Assisi. The stone is processed with traditional methods by the parishioners themselves. Inside the complex one can find a copy of Porziuncola - the Chapel of St Mary of the Angels, which functioned in Assisi in the times of the Italian saint. There is also a 1:1 copy of St Francis’s grave as well as an oratory built in the style inspired by Gothic architecture which will cease to be available to women visiting the place when the monks finally move into the monastery. If one managed to enter the round Mary’s chapel on Christmas night, they would be able to see the light of the Christmas Star shining through the opening in the middle of the stone dome.

Artykuł ukazał się w magazynie BEDRIFT jesień 2012.

A tourist walking in the vicinity of the monastery may have the impression that he or she has suddenly come across a medieval Tuscany abbey, with a charming path winding along its walls. In this way Tychy is no longer a more or less regularly planned centre of concrete residential buildings but becomes an interesting, multilayer cluster of various historical references, very much justified to be found in this place by the centuries-old tradition of Christianity in Silesia.